Travel Date: Wednesday, May 8, 2024

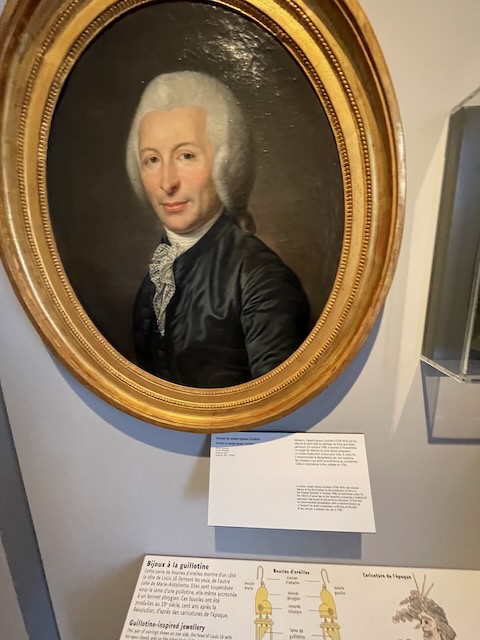

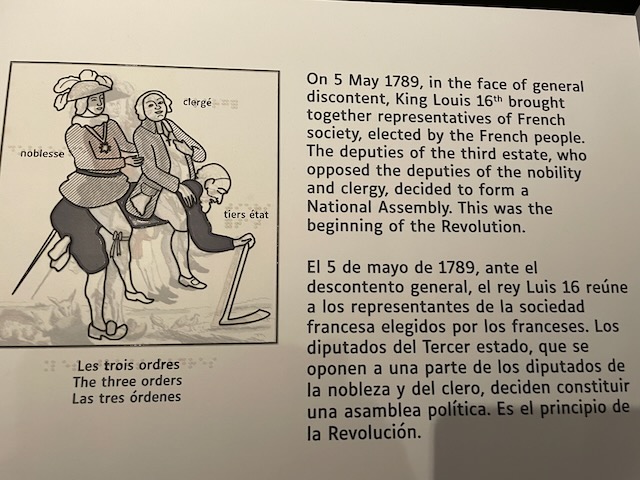

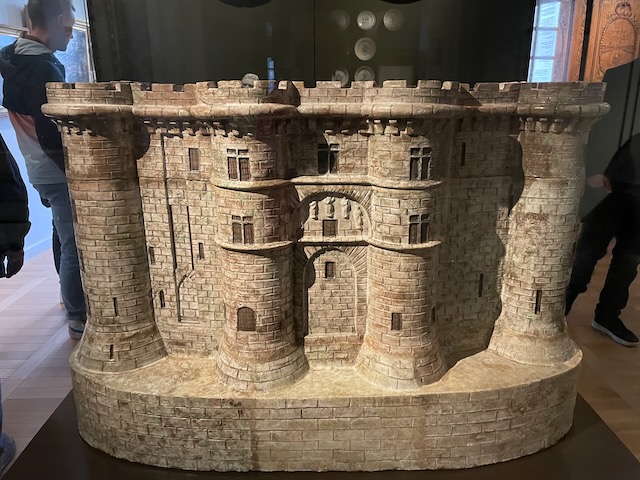

In the past few days I have written at some length about how I have wished that I had learned more about the history of France in general and the French Revolution in particular before I went to France, rather than after I returned to Canada, so that I’d have had a greater appreciation for the historical significance of several of the sites we visited. Among these were the Champs de Mars, a large green space southeast of the Eiffel Tower, where Bastille Day was first celebrated on July 14 1790 to mark the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille and where the first major massacre of the Revolution occurred, and Place de la Concorde, which was the location of many of the 17,000 public beheadings that took place during the Reign of Terror.

The Palace at Versailles also played a central role in the French Revolution. The primary impetus for the Revolution, which ultimately lasted for more than ten years and expanded from a civil uprising to involve several neighbouring countries, was the terrible social and economic circumstances in which most French people were living, largely due to the onerous tax burden that the “ancien regime” (“old order”) imposed on them. The economy was on the verge of collapse but in the meantime, King Louis XVI (a popular king) and his wife Marie-Antoinette (not as despicable as her reputation would have it, from what I have now read) were living with their son the Dauphin and other relatives in the most luxurious conditions imaginable. One early, unsuccessful attempt to quell the fomenting unrest took place at the Royal Tennis Court at Versailles in 1789, and it was from Versailles that the king and queen were moved to the Tuileries Castle in Paris and thence to prison and after that to their own public executions.

I highly recommend Hilary Mantel’s novel A Place of Greater Safety and the French Revolution podcast episodes of The Rest is History for fascinating in-depth explorations of this decade in French history – which did not go well at all but ultimately did lead to a democracy in France that has lasted till this day (and which we desperately hope will continue).

Where I was going with that draft, now revised to become this draft, was to draw comparisons between the social and economic conditions in France that precipitated the overthrow of the monarchy, then the failure of one replacement system of government after another, with conditions that are contributing to the popularity of far-right movements around the world today. But I decided that whole line of thought was too depressing, and also that it would take me weeks to research my argument to the extent that I could support it with citations, so (you’ll be relieved to hear) I’ve decided to just show you some of the many photos we took when we went to Versailles and toured the chateau. ‘ll leave you to crawl down the rabbit holes that lead to political parallels if you so desire.

.

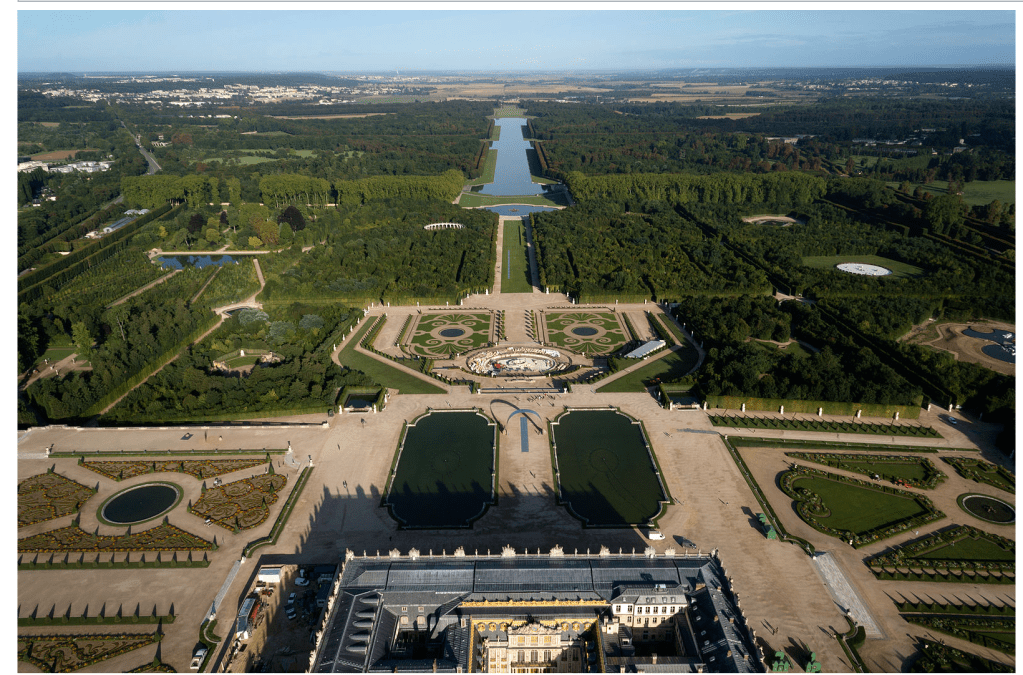

Versailles palace , which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was built originally as a hunting lodge in 1623 by Louis XIII, and expanded to its current massive size by Louis XIV. It was the latter Louis who moved the seat of the French government from Paris to Versailles (no. I will not mention Mar-a Lago here), and it was at Versailles where Louis XVI was living when all hell broke loose.

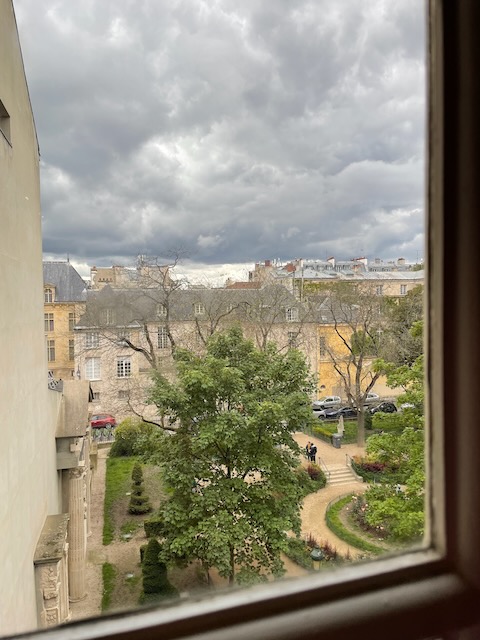

Today “The palace is owned by the government of France […]. About 15,000,000 people visit the palace, park, or gardens of Versailles every year, making it one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world” (Wikipedia). The Versailles experience begins as soon as you board the train that carries visitors along the 10.7 k route from Paris.

The walk from the train station to the palace takes ten or 15 minutes, which provides visitors an opportunity to begin to absorb the sheer size of the chateau and the vastness of the estate (800 hectares).

Early in our tour we saw the living quarters of Mme Victoire and Mme Adelaide, two of King Louis XVI’s sisters. They survived the Revolution, as did the Dauphin (who was later recognized by royalists as King Louis XVII, although he did not reign).

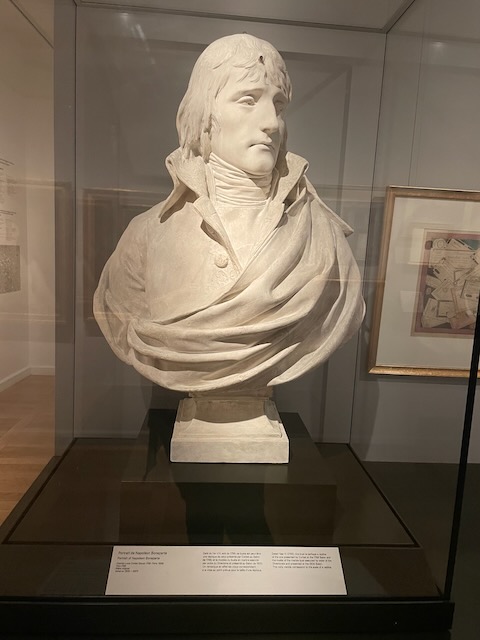

We saw sculptures in nearly every room of the palace, some strangely attractive and some really breathtaking. In the former category are the statuary shown in first four images below, which were formerly fountains with water spewing from their mouths and heads. The last two photos are of more classical statues, made from white Carrara marble. They date from the mid-1600s.

We visited the royal family chapel, which was larger and more ornate than many free-standing churches I’ve been in. There were also a lot of interesting paintings in the palace, not only hanging on the walls but also decorating the ceilings.

Versailles today is a museum. Not all of the art we saw would have been there during the reign of Louis XVI; some of the works were created long after he was relieved of his regal responsibilities.

The state rooms of the king and queen, including their private bedchambers, extended through nine or ten large rooms. Here is a sample:

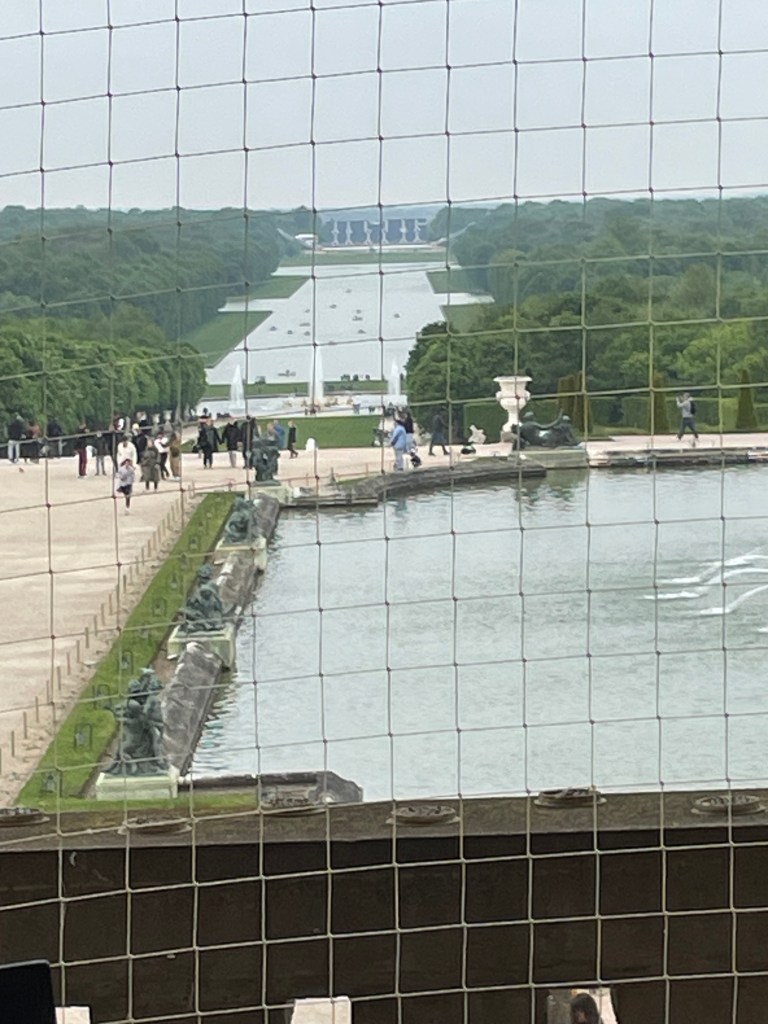

We saw the famous gardens at Versailles through many of the windows in the rooms we visited, but we ran out of time and energy before we could wander around outside

The Treaty of Versailles which ended the first world war was signed in the Hall of Mirrors on June 28, 1919.

.

After returning to Paris, we decided to eat dinner at Bouillon Pigalle restaurant. We had seen the long lines waiting outside this restaurant a few days previously and had become interested in eating there, but it seemed to have no accessible system for taking reservations. We decided that waiting in line must be worth it, since so many other people were doing that. The line is so long that it runs down the whole block and around the corner. Thanks to a special agreement between the restaurants, there is a break in the line in the middle so that patrons of the McDonald’s next door can get to their destination.

The wait was worth it, as it was so often on this trip. Le Bouillon Pigalle serves delicious French food in a very efficient manner, where patrons sit close to one another and orders are taken almost as soon as you’ve been seated. But the system works: there is no sense of being rushed, the food is excellent, and the price is reasonable.