Travel date: Monday, September 15, 2025

Some of the destinations on our Trafalgar Tour of Northern Spain seemed more incidental than essential. This was probably true in part because I was not there as a pilgrim, seeking out specific sacred sites. Zaragoza, for example, was just over half way between Barcelona and Pamplona – our ultimate destination for the day – so it was a natural place to pause for lunch and a stretch. But unlike Pamplona itself – or San Sebastian, or Bilbao further down the road – I couldn’t imagine that too many people would put Zaragoza on a list entitled “Places I want to see in Spain.”

As it turned out, the lesser-known (to me) centres we visited on this tour offered a whole range of fascinating historical, cultural, geographical and even culinary marvels. From those experiences, plus information I’ve acquired about other parts of Spain before and since (e.g., the other day I read somewhere about the Aranjuez Palace near Madrid, which looks quite spectacular), I have come to understand that no matter where you go, you are probably going to find some really interesting stuff to look at. Rather than making me want to get back on the bus so we could move on to the next notable destination, such places just made me wish we had about a year to poke around to see the stuff in Spain that isn’t in the tourist books as well as the stuff that is.

The Bus Trip

Zaragoza is about three hours from Barcelona, and about two hours from Pamplona. While recognizing that the very definition of “tour” involves the process of getting from one place to another, some people in our group did not enjoy the long travel days on our agenda. (Happily for one woman who was prone to travel sickness, these were relatively few in number.) I don’t mind spending most of a day on a bus or train: I fill such extended travel time quite contentedly by listening to a book while watching the countryside go by, and occasionally trying to photograph what I see (not always easy through a bus window. The reflection from the window itself often becomes an issue).

This is some of the countryside we saw as we drove from Barcelona to Pamplona.

Zaragoza

Zaragoza is the capital of the autonomous community of Aragon (Spain has 17 autonomous communities as well as two autonomous cities), and is also the capital of Zaragoza, one of three provinces in Aragon. As of 2024, the city’s population was about 680,00 people, which makes it the fourth most populous city in Spain. So while it may not be as famous as Barcelona or Madrid, it’s not exactly a whistle stop.

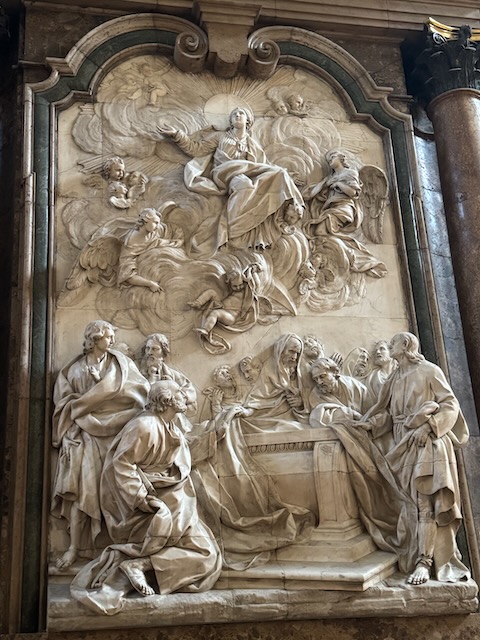

The city was founded more than 2000 years ago. Among its landmarks, it is known for: its Roman foundations; the Aljaferi Palace, a unique example of Islamic architecture that was built in the 11th century and is still in use as a government building; its Aragonese food and nightlife; and (especially) for the colossal Basilica del Pilar, a baroque cathedral with multiple domes and a shrine to the Virgin Mary. Thousands of pilgrims do make this a destination every year.

We did not see the Roman ruins or the palace, but during our visit we had time to wander some of the streets of Zaragoza, enjoy a delicious lunch at a kebab-felafel restaurant, and see the interior of the basilica.

Pamplona

In each town or city we visited, a “local specialist” took over the microphone from our travel director, Celia, and in almost every case these people were excellent resources – interesting, patient, and deeply steeped in knowledge about their particular regions. This is one of the initiatives Trafalgar has instituted (as, I am sure, have most reputable tour companies) to funnel some of the money paid by travellers into local communities. Other such practices include patronizing local restaurants and businesses, and making time at most stops for groups to visit local shops.

The specialist who guided us around Pamplona told us that the city’s residents credit Ernest Hemingway with putting Pamplona on the map. Indeed, I expect that I first heard of Pamplona when I read The Sun Also Rises in university. (I’ve just finished listening to it again on Audible, read by William Hurt. Hurt has the dry, uninterested voice that is perfect for Hemingway’s prose. I’d forgotten most of the plot, and I’d also forgotten that Hemingway was a racist antisemite, among his other flaws. Which is too bad because his evocations of Pamplona, San Sebastian, Biarritz and other places we visited, not to mention his tormented characters, are masterfully done, but I doubt most self-respecting readers want to put up with his debased and ugly biases any more.) Everywhere you look in Pamplona, the memory of Hemingway is interwoven with the story of the city.

The Bulls

When his book was published to great acclaim in 1926, Hemingway brought the literary world’s attention not only to Pamplona, but also of course to its bullfights and to the annual encierro de toros (better known in English as “the running of the bulls”). Largely thanks to him, every year thousands upon thousands of tourists come to the city during the Feast of Saint Fermin (July 7 to 14) to watch the spectacle unfold – and often even to participate. The fiesta is an important contributor to Pamplona’s economy.

Each morning during the fiesta, at least six bulls and six steers are sent running along a short route through the streets of Pamplona to the bullfighting arena. There, the bulls are penned up until it is their turn to “participate” in the bullfighting event that takes place later in the day. Every year, thousands of tourists and locals try to outrun the bulls during the encierro. Since the bulls are running at 25 k per hour (about 15 mph), staying ahead of them is no mean feat, and those foolish enough to actually allow themselves to be chased typically run out of oomph and make their escape from the fenced-off running corridor after only a few metres.

Our group was invited to guess how many of the two to four thousand people who have attempted to run with the bulls each day since Hemingway made the activity famous in the 1920s have been killed. Guesses were mostly more than a hundred. Turns out the number is 12. Their names are carved on the base of the “Monumento al Encierro,” a statue by Rafael Huerta that depicts the annual event. Many more than 12 have, of course, been injured, many seriously.

El encierro de toros has been part of the local culture for hundreds of years, and evolved (as did the spectacle of bullfighting) from the annual herding of the bulls to market through the city’s streets. Our local specialist suggested that the custom came about when some bright bull breeder realized that it was cheaper and easier to get the beef to market on foot rather than by trying to transport the huge animals on wagons.

At the end of the encierro, the steers (who are used like pilot boats; they are veterans of previous corrida and know their way through the city to the bull ring) are sent back home, and the bulls are corralled in stalls in the bullfighting arena. Later in the day, they are confronted in a battle to the death by matadors and their attendant picadores, rejoneadores, and banderilleros, the latter three groups being lesser participants in the bullfight who help to wear the animal out in preparation for the kill.

Bullfighting occurs not only in Spain and Portugal (as it has in one form or another since prehistoric times), but also in Mexico and several South American countries. If you are interested in learning more about the actual bullfight, there are plenty of resources available, such as this write-up on Wikipedia, but I don’t want to read them or see any videos that may be available, so you are on your own. Thanks in part to the work of a number of animal welfare activist groups, bullfighting is now banned in several regions of Spain, Mexico and South America, and attendance at such events grows smaller every year so maybe one day they will be only another unwelcome historic memory.

Pamplona is a lovely city (and again, so clean!). With our guide, we wandered the famous streets, and saw La Ciudadela (a Renaissance military fort built in the 16th and 17th centuries, which is now a park). Then we settled into the Iriba, the café and watering hole that features largely in Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises. The cafe has been preserved very much the way Hemingway would have known it. There we were treated to a drink (appropriate since Hemingway was a notorious drunk. I had lemonade) and an assortment of tasty tapas.

Signs and Symbols

It is a custom in Pamplona to mount a dried flower over doors of homes and shops to keep evil away. The ornament looks like a sunflower, and indeed it is called an eguzkilore, which is the Basque word for “flower of the sun.” However, this traditional protective symbol is actually the dried bloom of the wild thistle Carlina acaulis or Carlina acanthifolia.

The scallop shell symbol that is seen all over Spain indicates that you are on one of the many roads (caminos) to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain, where it is believed that Saint James is buried. Santiago de Compostela is a sacred destination for thousands of pilgrims, most of whom travel to it on foot each year from all of the regions of Spain, Portugal, France and other countries. (More on that later.) As you can see from the blue and yellow sign, the hinge of the scallop shell, where the radiant lines meet, serves as a pointer in the direction of the holy site. One of our guides explained that the symbol not only offers directions, but reflects the way in which pilgrims from all around the world meet at the sacred destination.