(In August, 1999, I took a one-day excursion from my first-ever visit to London England to visit the town in Wales where my father had been born. He died when I was 2 and I knew very little about him. Thanks to an amazing couple, Maureen and Terry Williams, strangers who extended an incredible gift of hospitality and friendship, I learned even more than I’d hoped about Abertillery and the beautiful valley in which it is situated. And thereby, about my father.)

“Is there a hotel in town?” I asked the driver as I hoisted my duffel bag, heavy with guidebooks notebooks a camera jeans nightgown toothbrush a sweater clean-underwear-and-socks onto my shoulder and prepared to disembark.

He looked at me as though I were daft.

“I’m from Cardiff, i’nnit?” he said (as in ‘How the hell would I know?’). But he made an effort on my behalf, repeating my question to three clear-skinned teenaged girls as they edged past me onto the nearly empty bus, their eyes on me as they let their coins clatter down into the box.

“Aw, noo. I doon’ think so,” said one of them to another.

“Maybe there?” said the other back to the first, bending to indicate through the bus windows a gabled, several-storied red brick building just below us.

“Nah. Doon’ think so,” said the third, speaking like the other two in a soft voice that rose, to me, in unfamiliar places and made her hard to understand.

The doors of the bus sighed shut behind me as I stepped onto the pavement. Soughing diesel down into the street, it moved slowly up the roadway toward the next town, then the next and then the next. At Brynmawr, it would turn around and begin its descent south through the Ebbw Valley back to Newport, the city on the Severn where—according to a letter that contained the biographical information I’d requested from the Saskatchewan Archives Board—my father had clerked for a time at a store named Pegler’s.

I stowed my valuables, which for now included my passport, travellers’ cheques, assorted bits of British and Canadian currency, tickets, a map, and a copy of that precious letter, in a side pocket of my bag, and zipped it closed. I lifted the bag onto my shoulder, and started down the deserted street toward the run-down building the girl on the bus had pointed out. When I’d descended the sidewalk to its lower southern side, I could see that the building’s entrance had long been boarded shut, but as I followed the sidewalk up again, I discovered on the building’s western hip the local library—a good place to have directed someone who needed information, except that it too was closed.

Now I saw that a man a bit older than myself was standing on the corner of the street ahead, above me, tanned and grey, his slender good looks set off by his uniform: navy trousers, a long-sleeved white shirt with navy epaulettes, a navy tie. I did not know yet that his name was Terry Williams, or that he was a well respected husband and proud father of two grown children who did odd jobs for neighbours rather than dip into the family coffers for his rugby-ticket money. Or that he’d retired after forty years of trade-work—never having missed a single day—then, finding himself at loose ends, had applied to become the local traffic warden, which meant that on some days like this one, he needed to stand for extended periods of time beside an empty road in his carefully pressed uniform in order to complete his shift. But he looked safe enough to talk to.

He watched my approach with a fair degree of curiosity.

“Is there a hotel in town?” I asked, lowering my bag to the pavement, then reknotting the elasticized band at the nape of my neck to keep my hair back.

“Noo,” he said, looking around, clearly distracted from wondering about me by his sorrow at my question. “Used to be.” He nodded down the street. “Closed now.”

“Motel, then? A bed-and-breakfast?”

He shook his head regretfully. “Nothin like tha’ here. Noo.”

I should have booked something before leaving London, but I’d wanted no reason not to come here on my own.

“I should have called ahead,” I said, to make it clear I wasn’t blaming him, or his town. “I came because my father was born in Wales. Here—” I waved my hand around, unwilling to try to pronounce the name of this place I had reached at last. “I never knew him, or any of his family. He died when I was two.” I looked around me, adding these deserted streets and buildings to the knowledge of my father that until today had mainly consisted of the typed, half-page list of dates and places I carried in my bag. It now also included the vast gold and dark-green valley I had risen through for nearly an hour on the local bus to get up here from Newport, and the soft, surprising way the people of this region spoke with a question behind nearly every sentence. “I came to see where he was born.”

“All the way from Canada?” he asked, astounded.

“I’ve been staying with a friend in London,” I told him. “I’m going back there tomorrow.”

“When would your father have been born?” he asked.

“In 1908,” I said, looking across the valley toward its western slope. I smiled. “I’m glad I came. It’s beautiful.”

“Wouldna looked like this back then,” he said with a shake of his head. “Hills were black in those days, from the coal.” He didn’t mean to suggest that these soft green slopes, the clear blue skies were an improvement. “Thatcher, i’nnit? Prime Minister back then? She closed the mines to punish the unions for the strikes.” He shook his head. “Now there’s no industry, no work. The place is dyin’.”

I reconsidered the green hillsides. “And there’s nowhere to stay.”

“Not in Abertillery.”

So, there: at last the name of the place was out—spoken aloud, caressed by his voice. My heart thudded into love with it—the soft stress on the second-last syllable, rather than the first as I’d been saying it to myself for all these years. “Aber” meant “mouth” or “confluence”—the only Welsh word I knew so far: I’d reached ‘the mouth of the Tyleri.’

“I think there’s a guest home toward Blaina.” He was pointing up the valley.

I lifted my bag again onto my shoulder, smiled and thanked him. He smiled back, but he wasn’t happy. “It’s at least five miles to Blaina,” he said. “You can’t walk all that way.”

“I’ll be fine,” I told him, starting off.

“It’s below the highway to the west,” he called after me disconsolately. “Just before the town.”

Cars and trucks zoomed past me as I walked along the highway—traffic headed, although I did not know it yet, up the way that one could go in the passenger seat of a battered little red Rabbit, through Blaina and Brynmawr to the Heads of the Valleys Road, then west to Tredegar. There, in the district office, a fifty-year-old woman such as myself could secure a birth certificate that would finally give her the full names of her father’s parents, and the address of his first home.

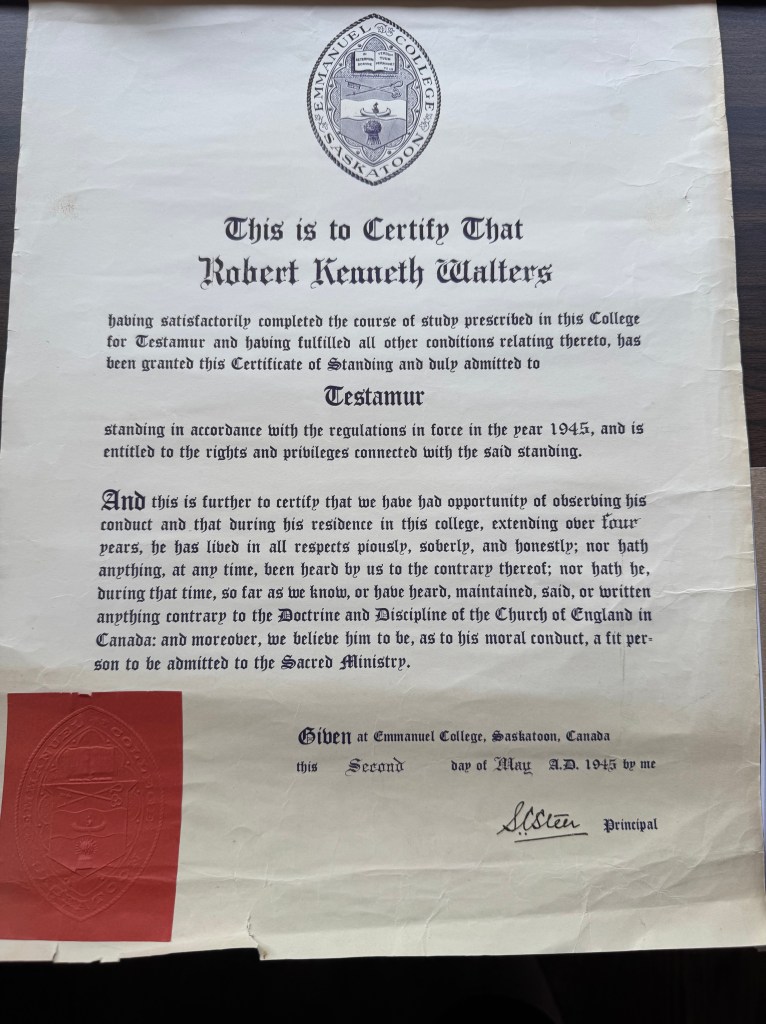

He’d left southern Wales at age nineteen, said the letter in my bag, “to get away from depressed industrial areas … where there were no business prospects.” He’d worked for Canadian Pacific in Montreal for twelve years as a bookkeeper, providing for his mother and his sister as well as for himself—the women having followed him to Canada after his father and his brothers died. My grandfather and my uncles, those men would have been: four of the thousands of Welsh miners dead through accident or disease because of where they’d worked.

Almost before I knew it I was out of Abertillery—“Aber-til-ler-y”—out of it but not beyond it. The town continued to rise up the valley’s eastern slope beyond the fences separating me from it, in terrace after terrace of joined cottages. Far off, a local bus made its way south through these residential areas and I wondered if it was the same bus I had taken up, now making its way back down again to Newport.

As I walked, I looked over at the jagged rows of grey brick walls, white siding, chimneyed roofs tiled grey and red, and wondered if this had been the street where he had lived—or maybe this? Or there? What I could not see, just over the Ebbw Fach River from where I walked, was Abertillery Park and the green stretch of grounds where my father’s love for the game of rugby must have been engendered and then nurtured. A man I’d tracked down several years before, a retired Anglican priest who’d gone to theological college with him in Saskatoon, recalled how he’d loved rugby—to play it as well as watch it. Recalled that he’d loved a beer when the game was over, good conversation, laughter. From such bits had I begun to assemble a man who might have been my father. Not that I understood him—what could there have been to laugh about, with his father and brothers dead in Wales, his sister dying shortly after she came to Canada, and now his mother mad with grief and rage because he’d gone off and left her yet again—this time to go to university? He was only in his mid-thirties by that time, but he had little time left for living—just a few years for marriage, fatherhood, a small-town-Canada church vocation—before his own death started to unfurl inside him. I was already older than he’d ever been.

I stayed far right on the shoulder, facing traffic. To my left, farmland fell away, then rose again into the distance. I’d never been in terrain like this—in a valley so wide and soft that it could hold a dozen towns and cities in its lap. I was walking with my map folded in my hand, having tried unsuccessfully several times to find the landmarks that would tell me how much farther I must go to get to Blaina. Gradually my pace slowed, my bag feeling heavier and heavier as I continued upward. What if I didn’t find the guest-house before dark?

But now the fences ended, and a roadway opened to my right. I took it, hoping against hope that the traffic warden’s directions had been wrong, but after several minutes I saw it was a private road to a business of some sort. There was no “private” sign, but as I would learn before long, “private” did not have the same meaning as it did in Canada. High above the town of Abertillery, for example, you could walk right out across a farmer’s field, stepping around sheep turds until you reached the radio transmitter at the top of the valley. There, your breath catching at the sudden view, you could look down into the town itself, and even down into the next town—Six Bells, that was, where one of the several local collieries had been (45 men killed in a coal-gas explosion there in 1960, 1000 feet below the surface)—then farther south until you were sure you saw the glint of the Severn in the distance. On your way down into town again, a hurtling descent around hairpin turns pocked with Rabbit horn blasts to warn off anyone who might be in the way, you could stop at a deconsecrated church—St. Illtyd. Parts of that building were a dozen centuries old: my father’s life, his father’s and the rest—brief even in human terms—were mere flecks against that kind of time.

I resumed my trek up the highway, growing increasingly discouraged. If I couldn’t sleep in the town where my father had been born, I might as well go back to Cardiff and find a room that was at least somewhere near the bus to London. I had done what I intended: I had found the town. I had even talked to someone who lived there, seen a street-corner or two, considered a few houses that might well have been his.

It is true that I had not yet been welcomed into a snug home on Cwm Cottage Road, or been shown up and down the valley before the dark descended; not been offered a feast of steak-and-kidney pie, mashed potatoes, peas, hot tea, or been given a comfortable upstairs room in which to spend the night. I had not yet begun to know two of the gentlest people I could ever have imagined, nor had I yet seen their willingness to share with a stranger whatever they could think of about her father’s birthplace—completely unaware that their gestures, their way of speaking and their generosity would show her as much about him as the rest combined. They would give her a piece of herself she hadn’t had before—and ignite a fierce pride in it.

Nor had I yet stood on a sidewalk just half a block off Cwm Cottage Road, looked up at a narrow house mid-terrace—29 Princess Street—where my father was born and raised – and imagined its tiled walls sifted over with coal dust, pictured its men hurrying off to the colliery, wondered how so many people could have lived in so small a place. I had not yet strolled through Abertillery’s weekly outdoor market—spread out in the morning sunlight on the cobbled church plaza as it had been for decades—and reflected on the determination of a young man who’d left everything familiar to come to an unknown country. And not just for a night. For ever.

I had done what I could. It would have to be enough. If I didn’t make a move soon, the buses down to Newport would stop running for the night.

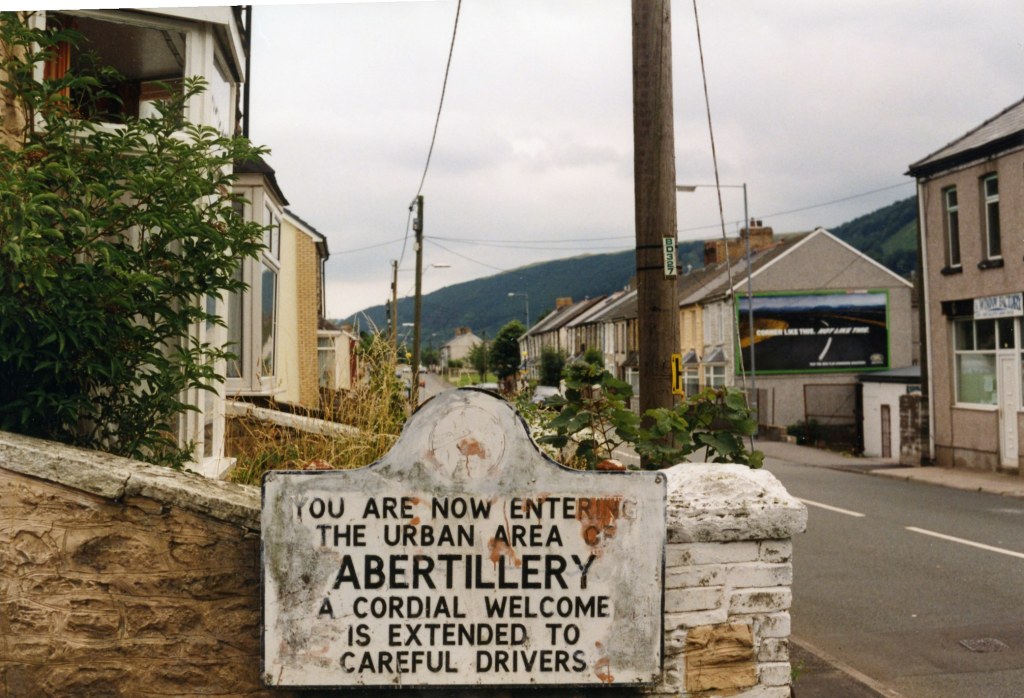

I cut down into the ditch, threw my bag over a fence and clambered after it, headed up a grassy hill to the road that led back to town. Back I walked through the deserted streets, until finally I saw a post with a bus-stop notice on it. But between it and me was a rusting white enamel sign that read, “You are now entering the urban area of Abertillery. A cordial welcome is extended to careful drivers.”

I had to take a picture. It would be proof, if only to myself, that I had actually been here. I put down my bag, dug out my camera, and crouched to take the photo.

As I did, a bus zoomed past, going south. I watched it disappear and felt something tighten in my throat—certain that I’d let the last bus get away.

But now, a small red car—possibly a Rabbit—zipped up the road from behind me, whipped over to the curb and stopped. The driver—a strongly built woman radiating energy, with soft grey hair in curls and a face with so much life in it, it revived me just to see her—clambered out.

“Are you from Canada?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, surprised, looking down—trying to imagine what aspect of my appearance could have given my nationality away.

“Thank God I’ve found you,” she laughed. “I’ve been looking everywhere! Get in. I’m the traffic warden’s wife: Maureen. I’ve come to take you home.”

*****

“Abertillery” was published in The Nashwaak Review in 2024. Below are photos I took in 1999 when I visited the town of my father’s birth in Wales.