Travel Date: Friday, April 26, 2024

On the first Friday of our trip, we made our way from Paddington to the Victoria Coach Station to join a day tour that would take us to Stonehenge and the City of Bath. The Victoria Coach Station is not, as one might have expected, attached to the Victoria Underground Station, or even to the Victoria Train Station (the latter two being adjacent and loosely connected) but is instead several blocks away. As it turned out, this was useful information for us to have as we would need to make two more trips to that same station before the conclusion of our time in England.

Boarding began at 8 a.m. for the 8:30 tour, and due to the unanticipated quarter-hour walk from the Victoria Underground to the correct gate at the Victoria Coach Station, we were hard pressed to get in a quick breakfast before we boarded. All of the departure-gate doors in the station are locked five minutes before departure in order to prevent people from being driven over by departing buses, which means that if you don’t board early, you are SOL. Also, you are not allowed to take hot food or drink on board with you. On our second tour from VCS the following week, the guide told us that the only downside of her job was the sad spectacle of late-arriving customers banging on the glass doors as they helplessly watched their tour buses driving away without them.

Soon after we pulled away from the station, I saw through the bus window an intriguing little building, decorated with shells, in a park. I learned through an online search that this is one of two huts built during a post-WWII redesign of Grosvenor Gardens (which is the name of the park) by architect Jean Moreux. The shells are from England and France, to symbolize English-French unity. The huts, which are still used to store equipment, are built in the French fabrique style.

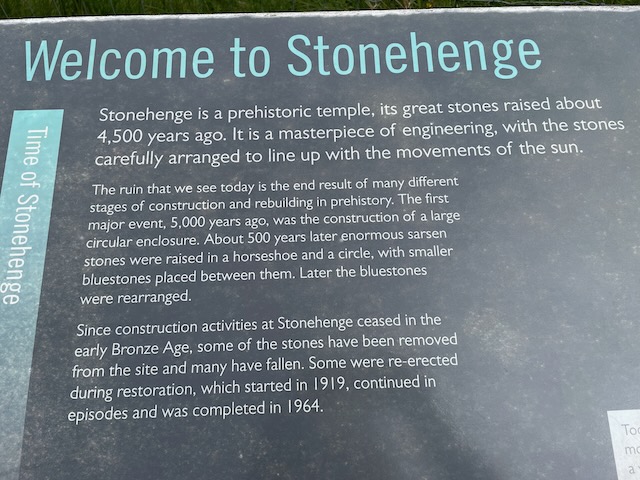

Two hours later, after travelling a little south but mostly west, we arrived at Stonehenge. Believed to have been constructed and in use from about 3700 to 1600 BC., the prehistoric structure is so famous that it must be recognizable to just about everyone on the planet. I’m sure I first saw photos of it when I was still in elementary school. Indeed, I think that much of the dramatic impact of catching a first sight of it (which is dramatic and worth the visit even if you’ve seen too many images of it already) arises from the site’s familiarity.

(Please click on photos to see bigger versions of them in a gallery format.)

Our visit took place on a cool and windy day but the sun was out and we took our time strolling around the site, trying to imagine how people several thousand years ago could possibly have gathered these immense stones together in one place – some from as far away as southern Wales – standing most of them on their ends and then hoisting the lintel stones into their horizontal positions. The upright stones, most of them “sarcen,” or silicified sandstone blocks, are estimated to weigh about 25 tons each. That’s the other part of the impact of visiting this place: the entire project seems impossible, but there it is, right before your eyes.

“Stonehenge is one of the most impressive prehistoric megalithic monuments in the world on account of the sheer size of its megaliths, the sophistication of its concentric plan and architectural design, the shaping of the stones – uniquely using both Wiltshire Sarsen sandstone and Pembroke Bluestone – and the precision with which it was built.” (UNESCO)

On Facebook, a number of people expressed regret that I did not get to see the site when it was still accessible to visitors. (“Back in the 70s, we could sit on the rocks!” they told me.) But once I realized what I was looking at, I was kind of glad that direct access is restricted. This marvel needs to be left alone so that future generations can see it too. Humans are always tempted to take away a souvenir or leave a mark, and in fact some of the graffiti on the stones already is hundreds of years old.

We learned that until the early 1900s, stones were still being removed from the site to be used as building materials elsewhere – another great reason for uncontrolled public access to be discontinued. It is still possible to walk into the site twice a year – during the spring and fall equinoxes – but it is necessary to sign up for these carefully controlled visits well in advance. In the meantime, the masses of tourists do not diminish the experience: even when hundreds of us were walking around Stonehenge, the site felt vast and unoccupied. It was easy to imagine how overwhelming the place must be when the visitors have left and only the stones (and the birds) remain. (I know, I know. Who would it overwhelm if there was no one there? But you know what I mean.)

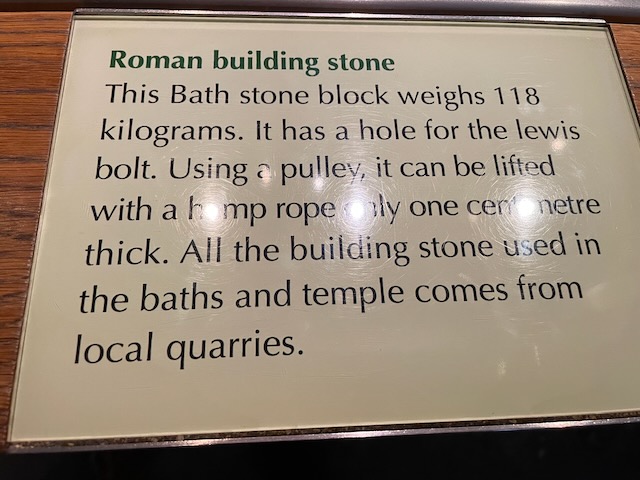

Bath

Our tour then moved on to the nearby city of Bath (33 miles from Stonehenge), whose buildings are almost all made from another local stone, this one with a lovely distinctive honey colour. (“Bath Stone is an oolitic limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate laid down during the Jurassic Period [195 to 135 million years ago] when the region that is now Bath was under a shallow sea”). Due to the hilly contours of the area and the proliferation of Georgian architecture, the town is picturesque from almost every vantage point.

The bus dropped us off in the main square of the city and a guide led us past Bath Abbey (1611; note the angels on the ladders at the front of the towers on each side of the entrance; oddly a couple of them are climbing down rather than up. I have found no explanation for the upside-down angels, nor for why angels might need ladders in the first place, but if you Google “Upside Down Angels Bath Abbey Ladders,” you’ll find some thoughts on the subject by other people) to the doors of the Roman Baths just down the street.

To be perfectly honest, I was mostly interested in seeing Bath because I had been so intrigued many decades ago when I read the “Prologue to The Wife of Bath’s Tale” in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in first-year English. The tale is distinctive not only because the narrator is a woman, but because her story speaks against “many centuries of an antifeminism that was particularly nurtured by the medieval church. In their eagerness to exalt the spiritual idea of chastity, certain theologians developed an idea of womankind that was nothing less than monstrous” (The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Vol. 1962). As a 16-year-old, this was one of my first brushes with feminist literature (even if it was written by a male who’d lived in the Middle Ages [1343-1400]).

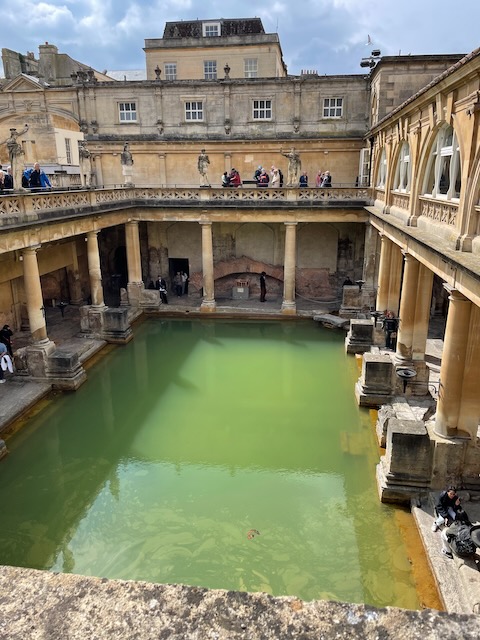

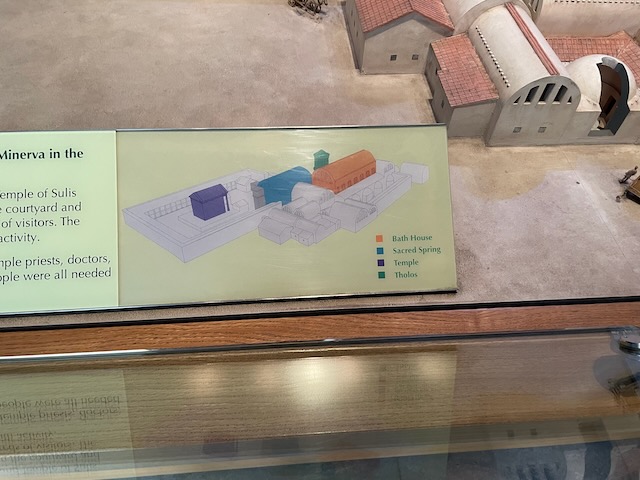

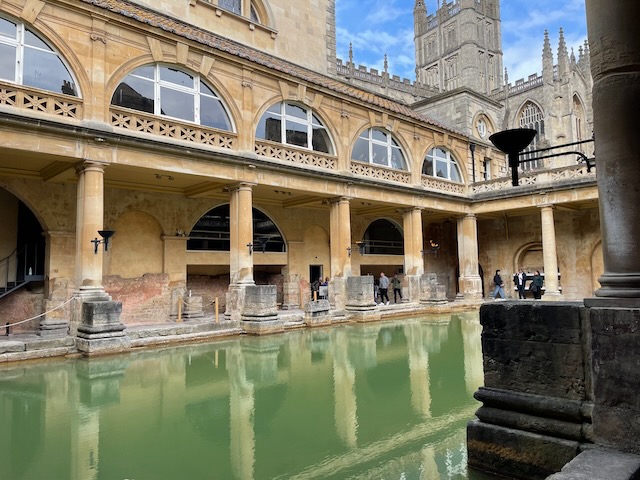

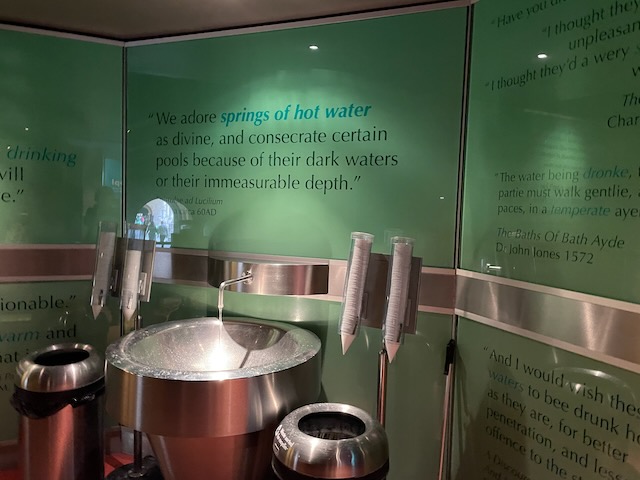

Somehow I’d missed realizing that the city had been named after the Roman baths that were built around the area’s natural springs during the Roman occupation in approximately 60 to 70 AD, and used until the Romans left Britain in about 500 AD. I almost didn’t bother to purchase advance tickets to the site, but I’m very glad I did. It is quite spectacular, mostly reconstructed in the 1800s to attract the interest of tourists. The lower level does preserve some of the features of the original Roman baths and, of course, the spring that motivated the Romans to build around it in the first place continues to burble up from about 10,000 feet below the surface. (“The hot mineral springs bubble up from the ground at temperatures well above 104 °F [40 °C], and the main one produces more than 300,000 gallons [1.3 million liters] a day” Britannica.) There is a very interesting piece about the Roman baths on Wikipedia.

Bathing is not permitted at the Baths, but I took a sip of the water and was immediately cured of everything except for my sore feet and aching lower back. Afterwards, we had a decadent ice cream waffle for lunch, while watching a woman get her hair styled on the street outside in front of a hair salon with a rather disturbing name. As far as I know, she emerged with her tresses trimmed and her brain intact. (Poor Nick. There must be a lot of teasing.)

Here are three short videos I took on the lower level of the Roman baths:

Discover more from I'm All Write

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I really enjoyed learning all about Bath and the Stonehenge description really showed how huge it is – thank you for sharing your experience!

Lovely description I had no idea about Bath’s history. Thank you for sharing your visit!

Very good. Thank you for sharing. Never wanted to go to Bath, but now I do. But if I can’t swim there maybe I don’t want to after all.

>

So happy to read about your Bath e perience. It brings back many wonderful memories of my other Merry friend ( Merlyn really , yes, also Welsh) and my visits with her there and